Who Was Harold Black?

Posted on Wed 03 September 2014 in tech

A little over a hundred years ago, some bright people thought it might be really useful for someone in New York to talk to someone in San Fransisco by telephone. They eventually succeeded in completing the first voice test of the system in 1914, and the first "official" transcontinental long distance phone call occurred in January of 1915. As is often the case, the first implementation of the system was really a prototype that would only handle limited load. The ultimate vision was a system that could handle thousands of voice calls simultaneously. There were large technical hurdles to clear to make that a reality.

One of the primary hurdles was amplification. If you want to string a very long wire and put lots of phone calls down that same wire, you have to place repeater amplifiers at points along the line that can boost the signal up without distorting it or adding noise to it. The amplifier technology of 1920 was not up to the task.

In 1921 a young electrical engineer named Harold Black joined the Western Electric Company, an arm of the Bell System, eventually to become part of Bell Labs when it was formed in 1925. Within several months of joining, Harold had succeeded in arranging an assignment to work on stabilizing and linearizing amplifiers to support the development of a large-scale long distance phone system. It would be several years before his work bore fruit.

Harold Black. (Source)

If you've studied dynamic systems or control engineering the names of Nyquist and Bode, also Bell Labs scientists in the early 20th century, are most certainly familiar. But Harold Black? You've probably never heard of him. Yet his invention revolutionized the telecommunications industry and had far-reaching consequences in other branches of engineering. Its impact can hardly be overstated.

What Harold invented is called the negative feedback amplifier. This classic video footage on the subject from the AT&T archives is worth watching:

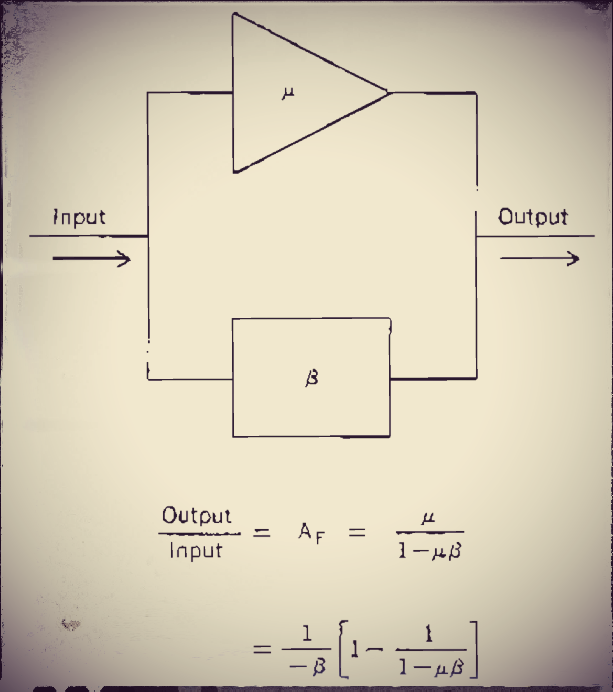

Aside: The hand sketches on newsprint shown in the video actually came five days later and relate to impedance matching the amplifier to the load. According to an article published in IEEE Spectrum, the sketches from the initial invention, also sketched on newsprint, were actually a simple block diagram and a couple of equations.

Negative feedback block diagram and equations. (Source)

For me personally, the invention itself is only part of the significance of this story. I'm forever grateful for Harold's candor in describing his years of unsuccessful design attempts and the flash of inspiration that ultimately accompanied the final breakthrough. This is his own written description of the event:

Then came the morning of Tuesday, August 2, 1927, when the concept of the negative feedback amplifier came to me in a flash while I was crossing the Hudson River on the Lackawanna Ferry, on my way to work. For more than 50 years I have pondered how and why the idea came, and I can't say any more today than I could that morning. All I know is that after several years of hard work on the problem, I suddenly realized that if I fed the amplifier output back to the input, in reverse phase, and kept the device from oscillating (singing, as we called it then), I would have exactly what I wanted: a means of canceling out the distortion in the output. I opened my morning newspaper and on a page of The New York Times I sketched a simple canonical diagram of a negative feedback amplifier plus the equations for the amplification with feedback. I signed the sketch, and 20 minutes later, when I reached the laboratory at 463 West Street, it was witnessed, understood, and signed by the late Earl C. Blessing.

With that, here is my personal recipe for changing the world while remaining in relative obscurity, modeled on the work of Harold Black:

Pursue opportunities that have the potential of making a serious difference in the world. Work on hard problems. When solutions don't immediately present themselves, keep going. Wait patiently for pure inspiration.

(An extended oral history of Harold Black's contributions is available from the IEEE History Center.)